Zhang Hongtu – A Retrospective at The Queens Museum

It takes a long time to find your way in a radically different culture, language and place. It takes humility and fortitude to figure out where you are and whether who you are will survive the disruption of transplanting. It takes imagination and determination, when you are illiterate in a new language, navigating a new map, to understand the people circling you. Their baggage of values, ideas, and notions of history. I know. I went off to live in Beijing when few Westerners had any idea about China. 1980. I know a little something about the frustrations, agonies and heart-breaks—and delights of discovery—when encountering another planet. That’s why I have been so intrigued by the life and art-making of Zhang Hongtu.

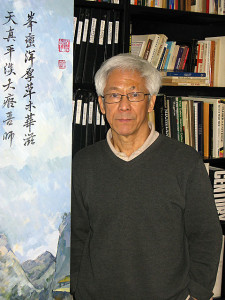

The Queens Museum in New York is currently offering a retrospective exhibit of this versatile, engaging and always surprising artist who has lived and created in New York City for the past thirty years. The exhibit features ninety objects in a breathtaking range of styles produced over the past six decades in Beijing and New York. Gigantic wall paintings, large conceptual objects, ceramic sculpture, mixed media works and paintings in a myriad of genres. A companion book— Zhang Hongtu, Expanding Visions of a Shrinking World—is edited by Luchia Meihua Lee (guest curator of the exhibit) and Jerome Silbergeld.

I first met Zhang Hongtu in 1985, not long after he arrived in New York City with a handful of other Chinese artists escaping the stranglehold of creativity back home. Some of them were from a dissident artist group in Beijing called “Xing, Xing” (“Star, Star”) and included the 23 year old Ai Weiwei as well as more mature artists like Yuan Yunsheng. These artists in exile had just written a manifesto expressing their concern about the current state of art-making in China stressing the connection between freedom and creativity.

Many of these transplants from Beijing had been assigned to factory jobs for life, not artistic vocations. Some had been banished to far rural regions during the Cultural Revolution or had witnessed their parents and grandparents persecuted to death. One had been punished for painting a bare arm on a portrait of a young girl. Another accomplished painter had been assigned to the boiler room of his factory for not conforming. He had fled to Tokyo.

At a time when few Americans had any interest in China and even less curiosity about Chinese artists, I interviewed these pilgrims for a lengthy feature in the Village Voice (“Is There Art After Liberation? Mao’s scorched Flowers Go West” http://gailpellettproductions.com/is-there-art-after-liberation-maos-scorched-flowers-go-west/

about the social, political and cultural upheavals their different generations witnessed and how they envisioned their journeys in the West.

Zhang Hongtu, then 40, had grown up in a Muslim family. His father, an Islamic scholar, set up Arabic schools around China, but was persecuted during the anti-Rightist movement of the mid-50s, then again during the Cultural Revolution.

In the 1950s Zhang studied at the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts in Beijing. The Academy’s approach to brush and ink painting as well as to Russian academic drawing was, according to Zhang, “copy, copy, copy so that every student’s work looked the same.” Whatever Western art that was available in books “was labeled bourgeois, decadent and bad.” Socialist Realism was the only acceptable style.

In that 1985 interview Zhang reported,“We had to copy without understanding the meaning of what we were doing. There were no whys, no understanding about what is art or spirit.” That mentality didn’t change during the Cultural Revolution, only the models, Zhang continued. “During that period some artists painted so many posters in one style, so many images of Mao, that afterwards they were unable to paint. It was both an artistic and psychological problem.”

During the Cultural Revolution Zhang spent three years working on an Army farm. While he appreciated what he learned about the world of the peasants, his complaint like so many other “sent down youth” was “There were no books! We were not even allowed to paint or draw.”

During the Cultural Revolution when his work was attacked and his best friend spied and reported on his diaries, he began to question the abuse of power. He later told an interviewer that “mistrust is one of the great sadnesses of China.” When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976 Zhang was assigned to a jewelry factory as designer. He had no say in this assignment, a job for life. He continued making art on his own and then applied for a visa for the U.S.

New York City in the early 1980s was a rough landing for a Chinese dissident artist who could barely flex the language, knew little about Western art and needed to support a family. Zhang’s wife found work as a designer in a textile factory. They had a young son. Zhang’s hair was already turning white.

Of that first group of adventurous artists, Zhang Hongtu was the one I empathized with most. He was my age. I had arrived in NYC in the mid-70s with few contacts or connections. Even though I was fluent in the language and culture, I knew something about how hard it was to find work and survive in the most competitive of American cities. I watched Zhang hustle construction work or carve giant Buddhas for a community center. He studied at the Art Students League while picking up odd jobs. He found a cheap studio in the East Village. But from my own experience in Beijing I knew that the deeper journey for Zhang would be psychological, intellectual and spiritual.

Although Zhang had trained and practiced art making before, during and after the Cultural Revolution, that practice seemed to have zero relevance to what he was looking at in New York. The giddy days of the East Village Art scene are nostalgic now, but back then the talk was of Neo-everything. Neo Expressionism, Neo-conceptualism, Neo-Geo. Jean-Michel Basquiat—known then as SAMO—was decorating the walls of buildings with his bizarre signs, having a dialogue of sorts with Keith Haring. Cindy Sherman, Julian Schnabel, Jeff Koons, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger (I Shop Therefore I am) and Robert Mapplethorpe were all vying for space. The excitement was in the alternative art spaces of the East Village not the uptown museums and galleries. This was the chaotic explosion of expression Zhang encountered.

Unsurprisingly, the pieces in the exhibit from his first years in New York reveal a dark mood. Shadow characters create a mysterious tension. They reminded me of a visit to his unheated East Village studio in 1985. As Zhang moved around huge paintings in thick ebony black paint with sketchy brilliant red line drawings on top depicting human figures, oxen and boulders, he said, “In China I never thought about the psychological part of painting. Here I am trying to move from my heart to an idea.”

Pondering these large expressionist canvases influenced perhaps by the current neo-expressionist styles in vogue in 80s New York, I thought they evoked stress and alienation. “They represent my feelings in New York, “ Zhang confessed.

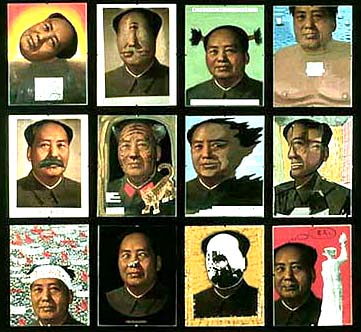

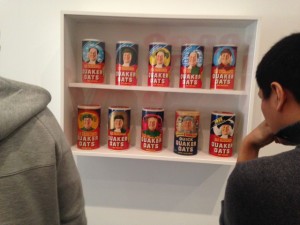

As the 80s progressed Zhang began wrestling with iconic images from his own culture as well as the one he had plunked down in, turning his focus to images of Mao, first as a series of negatives or cut-outs in mixed media using common materials like plywood and burlap. Next he was painting Mao’s face over top of the iconic man’s face on Quaker Oats boxes. In the exhibit we see Mao’s ubiquitous visage in many of Zhang’s conceptual productions. In one construction Mao is peeking from outside—watching— through a keyhole in a NYC apartment door with its multitude of locks. As if, even in New York, Zhang cannot escape his power and legacy.

When I interviewed Zhang in 1985 he said that he used to agree with Mao’s dictum that “art should serve the people,” but, he asked “was socialist realism the only style people can understand? Abstract art now worried Zhang less than Mao’s abstract concept of “the masses” and “serving the Communist Party.”

Eventually Zhang’s grounding in European concepts of drawing and painting – a legacy of Russian art training in China – along with his background in classical Chinese brushwork would serve his imagination once he found his voice in the New York cacophony. What ignited Zhang’s art-making was his consciousness of being an outsider—both in China as a Muslim—and in the West.

Zhang’s experience as an immigrant struggling to survive in New York along with his ongoing exploration of Western art and history, energized his creative output which became more sophisticated and playful simultaneously. The exhibit features a series of soy sauce paintings on pages of the New York Times whereby Zhang is pointing to the contradictions in the American promise of prosperity with the hard-scrabble experience of most immigrants. In this work, like many of his pieces, using common materials like rice, grass, burlap, cement and nails, he seems to mock our concerns with high and low art while pointing to the distance between reality and illusion.

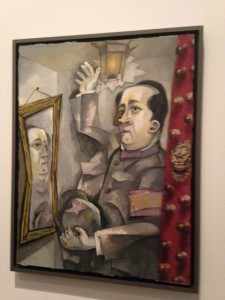

As the years sped by Zhang continued to pursue his critique of tyranny and authority in his mischievous images of Mao. The 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre inspired a fresh look at the legacy of Mao and raw power. Zhang’s painting, The Banquet, mimics da Vinci’s The Last Supper, only now all the faces are Mao’s. Zhang is mocking Mao’s strategy to concentrate power by killing his enemies and surrounding himself with sycophants. He seems to be implying that all those around Mao want to behave like him. It provokes us to think that it was Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, who sent the troops into Tiananmen Square. Zhang is implying that Deng wants to be a new Mao. All powerful.

In a more literal take of the painting, he seems to be criticizing the banquet tradition in China, particularly in the power center of Beijing, that squandered huge amounts of money entertaining privileged power elites.

Zhang continued to explore his dual situation of being from the East in the West. His knowledge of Western art history combined with sophisticated techniques are evident in a series of traditional Chinese landscape paintings executed in a variety of European styles. This melding evokes great western painters and Chinese masters. East fused with West.

Zhang explains, “In my art, I try to make a way through the wall, to put a door, a hole in the wall, by using Western art with my own art. There’s a Chinese saying, ‘You can’t breed a horse with a cow.’ My work is the opposite, like daring to breed the horse with the cow.”

Credited with starting the “China Pop” movement, Zhang’s retrospective exhibits tremendous diversity in work that is both provocative and humorous. And it reveals a continuing concern with unaccountable authority.

A large construction from 2015, The Big Red Door, refers to large red doors dotted with nails that indicate passageways everywhere in the Forbidden City. In his typical mischievous approach, Zhang has turned the nails on this piece into phalluses – a reference on his part to the patriarchal power that continues in China and elsewhere in the world.

Zhang’s work has shown in museums and galleries in Europe, the U.S. and Asia. Some of his iconic Mao pieces have appeared on the cover of U.S. news magazines. The Queens Museum exhibit will extend to February 28, 2016.

6 thoughts on “Zhang Hongtu – A Retrospective at The Queens Museum”