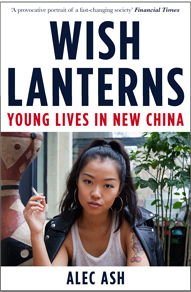

Young Lives in China – review of Alec Ash’s “Wish Lanterns”

Originally published in LA Review of Books: Dec. 2, 2016

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/young-lives-new-china/#!

AMERICANS ARE OFTEN highly opinionated about China, yet reveal an embarrassing ignorance about the Chinese. Alec Ash’s new book Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China is the antidote — a masterfully crafted collection of interwoven portraits of six young Chinese. Three men, three women. Millenials born between 1985 and 1990. Their journeys from childhood, balancing parental expectations against personal desires, hopes, dreams, achievements, and stumbles. And although it is not a political book, at its deepest core lies the question of dissent.

Ash reminds us that there are over 320 million Chinese in their teens and 20s in mainland China. “This is a transition generation, the thin end of the wedge that will change China, whether slowly or suddenly. Millennials coming of age as their nation comes into power.”

Ash warns us that the young people he profiles are not representatives or spokespeople for their generation. They all acquire university degrees and aspire to live in Beijing, the nation’s capital. There are no minorities here, they are all Han. There are no Chinese who now live abroad although one, the privileged daughter of a high Communist Party of China official, had the opportunity to do postgraduate studies in the United States. None are admittedly homosexual, bisexual, or transgender. But through the telling of these six stories, Ash cleverly weaves information about demographics, government policies, political history, as well as social and cultural trends.

I have to admit that I had an ulterior motive in reading this book. I had lived and worked in Beijing in 1980 and 1981, when Western diplomats, journalists, scholars, students, and tourists were just beginning to take a peek. China had been closed for 30 years. The Cultural Revolution had just ended four years earlier. And traumas suffered during that dramatic upheaval were just beginning to appear in literature and movies. All resources were rationed: food, clothing, and housing. There was little or no job mobility. Your work unit controlled where you lived, dispensed ration tickets, and granted permission to marry, give birth, or divorce.

All of that is ancient history. That China has been eclipsed by the economic boom that began in the 1990s and continues today, accompanied by the greatest movement of people from the countryside to the cities in global history. I couldn’t imagine any continuity between “my” Beijing and the contemporary experiences of Ash’s gang of six. And I was ready to judge them before knowing squat about their lives — believing they would be apolitical, apathetic, and focused on getting rich. I also suspected that because of government censorship — the many forbiddens — they would be ignorant of the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square protests and aftermath.

What I discovered in reading these compelling stories was a more complicated set of life trajectories. Some of my assumptions were partly fulfilled, particularly the amnesia or ignorance of revolutionary and resistance history (of course, they share that with many American students), but I was surprised by the continuity of issues from early 1980s Beijing — problems their contemporaries also face in the United States.Ash’s youthful cohort were all only children, all from the first generation of the one-child policy. Pampered initially, they were then disciplined rigorously to study for the brutal college entrance exams in order to secure a place in a university. Expected to succeed there, then find employment and marry. All this by the time they reached their late 20s.

Back in 1980, the universities were just beginning to rebuild after the crippling decade of the Cultural Revolution, when schools were closed or reduced to slogans from Mao’s Little Red Book and many university facilities were destroyed, and professors beaten or killed or humiliated into suicide. At Radio Beijing, where I worked, we reported on the new “television universities” where Mao’s Red Guard generation who had been sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution — now in their mid-20s and returning to the city — could sit in giant warehouses watching TV lessons, trying to make up for some of their missed schooling. It was a daunting effort and there was much talk of a “lost generation.”

The economic boom of the 1990s and 2000s have provided an opportunity for more young Chinese to attend university than ever before and several of the kids profiled here are the first in their generation to have that opportunity. The problem for today’s millenials, with their improved schooling and vast array of options to study after high school, is that once armed with their degrees, there are not enough jobs. And most jobs available pay miserably. All of Ash’s characters struggle with finding appropriate work for their studies, and most important, making enough money to afford to live in Beijing. Sound familiar?

Several stress lines that Ash bores into resonate with my period in China. The most obvious is the frustration of finding housing in Beijing. In 1980, no new housing had been built since the early 1960s. From the early 1980s to today there has been a steady and then explosive focus on creating new high-rise apartments for a population in the capital that keeps ballooning. Yet for young people today, Ash writes, most rents and certainly sale prices of apartments are out of sync with their meager salaries — even if they can find work. One of the characters who has a good job with a state construction company, still sleeps in a workers dorm (1980s workers would recognize that situation and its cramp on personal, romantic, and intimate lives) and another sleeps in one of the endless, windowless basement cubicles created for the urban working poor in the subterranean layers beneath the new high-rises, where it is easy to read the physical hierarchy of class and status. Another commutes two hours by bus to the fringes of Beijing to find something more humanly palatable and affordable. That’s where legions of Beijing’s young working force and its unemployed live. I am thinking of the march of New York City’s youthful workforce moving further and further to the far reaches of Brooklyn or leaving the city altogether because of real estate prices that don’t jive with their service-economy wages. Young people in Beijing — like those in the United States — confront an increasingly unequal economic landscape.

While Ash’s lens traces the idiosyncrasies of each of his characters’ path to adulthood, one common theme is the parental and societal pressure to marry by your late 20s. It is especially heavy-handed for women, and exacerbated by the gender imbalance caused by the one-child policy. In a traditionally patriarchal society, boy children were preferred, so there is now a ratio of roughly 118 men to every 100 women. In the meantime, many young women are going off to college or earning their own money and are less interested in early marriage. The Communist Party of China has been merciless in its pressure on women. The term “left-over women,” Ash tells us, was actually coined by the official All-China Women’s Federation that is closely tied to the party. During Mao’s era, the federation promoted women’s rights to equality with the famous slogan “Women Hold Up Half the Sky,” overseeing a sea change in many women’s lives with rights to education, jobs, and divorce, along with government child care.

At Radio Beijing, I worked on a program about the government’s revision to its 1950 Marriage Law, which granted women the right to marry whom they wished and to divorce. The 1980 revision recommended that young people delay marriage until their late 20s and to reconcile rather than divorce. Both recommendations, one colleague explained, were driven by the most pressing problem of the time — the housing crisis.

We are left to wonder about the government pressure today. Are they concerned about the dangers of an unsatisfied population of bachelors or women gaining too much power? Are they nervous about the urgency for a new generation of workers to fuel their economy, and therefore need women to settle down and become mothers? Is it still a housing issue? Old-fashioned patriarchy? Nostalgia for traditional women’s roles? That everlasting concern of the Communist Party — stability and harmony? Most likely a tangle of all of these things.

Back in 1980, I interviewed a group of English-speaking journalism grad students — all in their mid to late 20s — about romance, premarital sex, marriage, and divorce. Their responses to sexual questions were conservative by today’s standards — at least those revealed in these six portraits of millennials. While premarital sex was absolutely taboo in 1980 and Youth magazine published articles with titles like “Honor Your Virgin” and recommending cold showers to young men, Ash’s cohort feels free to bed down when they have an opportunity. The greater problem is finding a suitable mate to marry, especially for the men.

When the subject of marriageable partners came up for the 1980 journalism students they argued that young couples should consider political compatibility in making the right choice in a mate. During the Cultural Revolution, some husbands and wives had betrayed each other, leading to exile, prison or worse, and families in ruin. But as I listened to these students, something else was already at play — the desires unleashed by Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform (literal English translation from Chinese: opening and reform) policies. Young women in the 1980s were starting to judge an ideal husband prospect on whether he had, as the saying went, four things that went round: a watch, a washing machine, a sewing machine, and a cassette player. Three and a half decades later, the pressure for a potential groom is to have a job, a flat, a car, and savings. All of Ash’s male characters struggle with those material standards of success and desirability.

By far the most colorful stories in the book have to do with the cultural behavior of these six individuals and the trends that seduce or repel them. They are the first generation of netizens, gamers, cosplayers (yes, my senior comrades, look that up!), skateboarders, graffiti artists, tattoo boasters, punkers and rockers, barristas, fashionistas, and small-business owners. And it is here, in the cultural realm, that rebellion finds space. It may be in the rejection of being predictable “ant people,” college grads who commute like sardines long distances to work at underpaid jobs. They are mostly outsiders — not from Beijing — and live at the edges of the city.

The Chinese love for coining names is an insight into Mandarin culture — the delicious interplay of characters that are similar in design but with different tones imply different meanings. Ash tickles us with this new vocabulary. Those living in the windowless underground basement cubicles are called the “rat tribe.” There are also the “working grunt tribe” and “urged tribe” — the nine-to-fivers pressured into conformity — and the “bite the old tribe” living off mum and dad. All of this naming implies a critique. A consciousness of conformity versus nonconformity.

If the language offers up an ecology of resistance, the more profound venue of that rebellion exists online. “There was no justice but keyboard justice,” Ash claims, as at least one of his characters (Dahai) takes to the web with millions of other netizens to complain and protest corrupt cadres, environmental degradation, forced late-term abortions, or major infrastructure accidents that the Communist Party would like to literally bury. Ash argues that the underlying grievance of the netizen activists was social inequality and their anger at the riches being carted off by the party and business elites. For them, the system felt rigged.

Occasionally the online protest manifested itself physically in the streets. Usually only outside of Beijing — in the capital the consequences would be too serious. We learn that the only street protests permitted by the Communist Party are nationalistic outbursts, usually against Japan.

While it has been censored and blocked by an ever-tightening firewall, the creativity unleashed by this generation in couching politically forbidden references in a new vocabulary is mindbending.

Xi Jinping’s coming to power in 2013 put an end to much of the creative resistance in blogging by defanging Weibo and arresting those who used forbidden language. Then technology changed again. WeChat (like WhatsApp) became the new communication vehicle. More personal.

By far the most sophisticated exploration of political consciousness comes with Ash’s story of “Fred” (the English name for a daughter of a high party official who pursues a PhD in politics at Beijing Normal University). Through her evolution — which includes joining a campus Christian discussion group for a while — we see how ideology works. She leans toward different perspectives on campus: free-market neoliberalism, central authoritarian control, and Mao-era egalitarian idealism. When Fred does postgraduate work in the United States — to study the American constitution — she is attracted to some American values and legal protections, but she concludes that systems that work in the United States wouldn’t necessarily work in China. She, like the Communisty Party, fear they would lead to chaos. Perhaps more revealing is her conclusion that the US and China have much in common: “Both had a strong sense of exceptionalism. Both wanted to be number one. Both were obsessed by personal and national quests for money and power.”

If there is a frustration with the book and its gaggle of characters, it’s my desire for at least one of them to tap into the riskier territory of dissent. In the West, we hear about human rights lawyers who have been jailed, journalists who have lost their jobs or quit over government heavy-handed censorship, journals closed down, feminist activists who have been arrested for raising issues of women’s rights. None of Ash’s cast indicate any interest in these events.

Perhaps I only want one of Ash’s protagonists to acknowledge the courage and ideas of former generations of dissenters. When I arrived in Beijing, the democracy movement had just been crushed. Wei Jingsheng, the most eloquent voice of that movement, had just received a 15-year jail sentence for calling for democracy and referring to Deng Xiaoping as the new dictator. Artists were marching in the street for the right to free expression. Most of these actors were former Red Guards. Many participants in the Beijing Spring movement went on to lead or participate in the Tiananmen Square protests. They were part of a continuum from the student-led May Fourth Movement of 1919. Where is that impulse in China among the millenials? Or am I missing what Ash is trying to tell us with his selection?

The richness of Ash’s book is in the character development, the details of everyday life, dreams, frustrations, and contradictions of these particular individuals. Ash enters their worlds as a peer (he is their same age) and he’s a sensitive listener, reporter, and storyteller. Through this particular constellation of players, we sense that the fact that China is gaining strength in the world complicates their instincts for rebellion and resistance.